On 2 April, the US announced a reciprocal tariff policy imposing a universal baseline tariff of 10% on imports from all countries (beginning 5 April) and steeper tariffs for approximately 60 countries, with rates of as high as 50% for large surplus-holding nations. For example, the baseline tariff rate announced for Japan was 24%; for China, this rate was 34% (in addition to its existing 20% tariff), 32% for Taiwan, 20% for the European Union and as much as 46% for Vietnam. The structure of the tariffs appears to have been broadly received by markets as a limp and purposely feeble foray into quasi-empiricism, taking clear aim at trade surplus holders, many of which are geographically located in Asia. These surplus holders, by the same token, are the world's largest reserve holders, with a significant portion held in US dollars. Moreover, these tariffs are separate from, but not additive to, product-specific tariffs on items such as automobiles and steel.

On initial inspection, the announcement appears signal more aggressive than initially priced in by markets, leading to additional stock market sell-offs in equity markets across the globe. However, we had been cognizant of the potential for additional stock volatility in our quarterly outlook (see Global Investment Committee's outlook: regime shift to a more volatile world ). Given that the US certainly appears to hold a dominant position in global trade, it might be tempting to conclude that the rest of the trade-dependent world is doomed. However, we maintain that there are opportunities in the current sell-off for those able to withstand interim asset volatility.

A war on comparative advantage means less open trade

Some countries and industries are incontrovertibly more exposed to the initial actions taken by the US in what is now perceived to be a rapidly escalating trade war. For example, China faces significant economic repercussions, with estimates suggesting a decline in GDP growth due to ongoing stagnation in areas beyond exports such as domestic consumption and investment. This would make Beijing's 5% annual GDP growth target difficult to achieve. However, compared with Vietnam, whose trade to GDP ratio in 2023 was 166% , or the EU (which was 96%), China's trade to GDP ratio was only 37% according to World Bank data, and it has already made opening moves to support domestic demand growth. The focus remains on retaliatory measures, which almost certainly would damage growth for all sides in the current multi-lateral game, but also on measures that surplus-holding nations may take to shore up domestic demand growth.

Uncertainty over potential outcomes may increase the appeal of retaliation

The reason why the US may be perceived to remain in “game” mode is that the current administration's muscular measures have also been announced as an invitation for nations targeted by tariffs to propose “phenomenal” offers of new US-specific trade privileges. However, the game is a high-stakes one for the US because, despite Washington's perceived motivations, there are empirical estimates that the US consumer is likely to be a notable victim of an ensuing trade war.

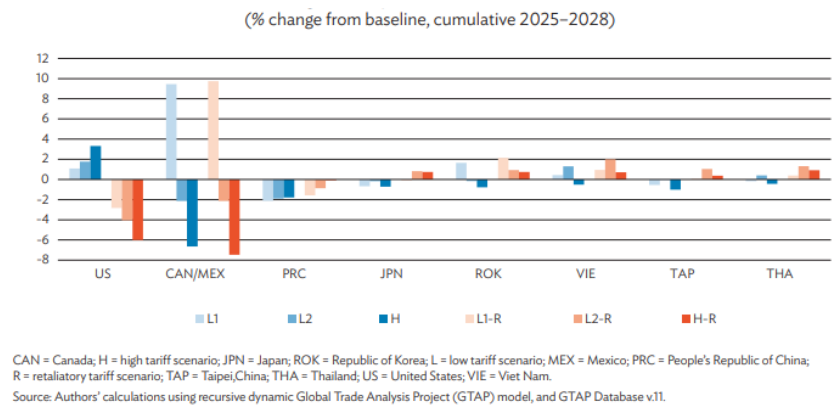

In the ADB's analysis of US tariff scenarios at the beginning of 2025, all scenarios resulted in the US achieving its near-term goal of shoring up its exports (Figure 1 of the linked report ). However, both production and real GDP are estimated to decline under all scenarios (Figures 3 and 4). The impact of tariffs varies significantly depending on whether retaliation occurs. All scenarios that feature retaliation are consistent with negative estimates of nominal income, which is particularly problematic when inflation is positive, while those that feature no retaliation show positive outcomes. In terms of payoffs, it still remains far from certain how much the US stands to gain from commencing a trade war. However, it can be said that the US's largest trade partners know in advance that they can hit US households and voters where it hurts, with the pain intensifying as trade barriers escalate (as illustrated below). Meanwhile, for trade partners, who also stand to suffer if they retaliate, the credibility of their threat lies in the potential that retaliation from multiple countries may hurt the US consumer more than it may hurt any individual retaliating economy, thus creating incentives for the US to back down from its initially more belligerent stance.

Chart 1: Impact on nominal income

Source: ADB Briefs No. 332 January 2025

Borrowing from game theory, one of the characteristics of multi-stage games is that strategies only reach equilibrium if they do not involve non-credible threats. In this sense, even though the true payoff for the US's apparent commencement of a trade war is unknown, both the US and its trade partners recognise that the threat of retaliation is credible, which enhances the bargaining positions of trade partners. Whether trade partners actually retaliate or simply threaten to do so to enhance their negotiating leverage, the temptation to draw out the trade hostilities or at least threaten retaliatory tariffs is real. At the same time, the US faces credible threats to the livelihoods of its households, which is one reason why it is a high-stakes strategy.

Higher stakes for the US private sector too

Borrowing once again from game theory, this time in the context of multi-stage games with complete but imperfect information, governments and firms can be seen as different players in the same game. Governments, via tariff strategies, move first, followed by firms, which take tariffs as given and try to maximise their profits in anticipation of their competitors' response to the tariffs. In this case, it is very possible that firms will produce less in aggregate than they would under a zero-tariff (or lower tariff) strategy.

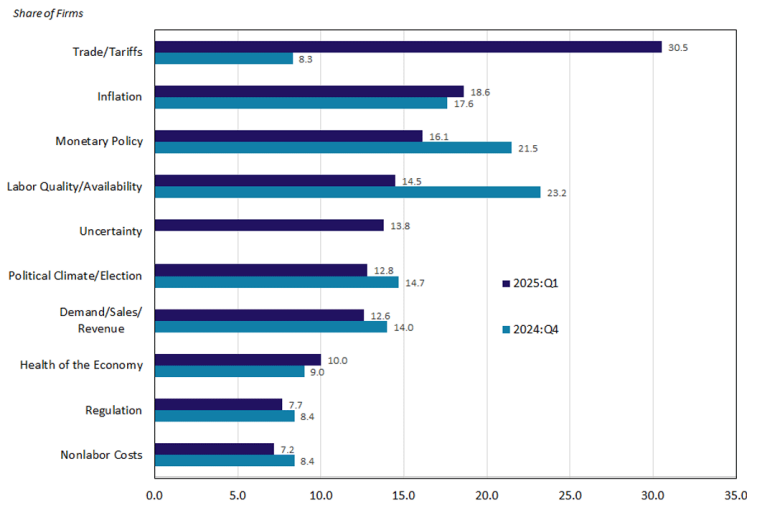

Moreover, it is possible that policymakers may possess confidential information about future tariff policies that firms do not have, making the game reliant on the degree of belief that firms have about future government policy. If firms decide that the risks of being wrong about future government policies outweigh the potential benefits of investing in future capacity, they could withhold investment or hiring, choosing to hold cash until policies become clearer. Such a cautious approach would add an extra high-stakes element to the game, potentially resulting in a slump in US investment. A Richmond Fed brief highlights that as of Q1 2025, Trade/Tariffs surpassed inflation concerns as the most pressing issues for CFOs.

Chart 2: CFOs' most pressing issues

Source: Richmond Fed, Tariffs: Estimating the Economic Impact of the 2025 Measures and Proposals

The same analysis points out that the US, for most of its early history, was reliant on tariffs for federal revenue before the introduction of the income tax in 1913. Yet as we point out in How Japan can safeguard against US tariffs , the last major attempt to reintroduce tariffs as a mainstay of federal income, the US Tariff act of 1930, backfired in part due to retaliatory measures taken by global trade partners. CFOs are probably justified in viewing the US tariff strategy not only as high-stakes but also a top problem area for firms' financial decision-making.

Message to surplus holders: that rainy day is here

One of the reasons not to write off the economies of the world's surplus holders—apart from the latent capital inherent in their ability to threaten retaliation—is that their surpluses represent many years of accumulated savings. These savings are often “recycled” into US dollars (USD), therefore providing financing for US consumption. One country's current account surplus is another country's current account deficit, which means that capital flows from surplus holder to deficit holder. We might look at the store of the USD 12.75 trillion in global foreign exchange reserves, of which over 57% are estimated to be denominated in US dollars. This proportion significantly exceeds the representation of the US within global trade. Historically, the US has been an exporter of capital, in turn consuming a surplus of goods and services from the rest of the world. However, the US is now seeking to punish its surplus-holding trade partners by attempting to reduce its consumption of their exports. The message to the rest of the surplus-holding world appears to be that the US has limited interest in continuing its role (and its exorbitant privilege) as the consumer of last resort. This also sends a clear message to surplus holders that the moment has now arrived to shift their many years of reserve-building and insulate their own economies. The world's reserve holders have the capital to do so, though for the moment most of the capital is denominated in US dollars—a currency used for producer inputs such as oil and commodities rather than consumer goods in markets outside the US.

Surplus economies have an incentive to shift their focus from production-focused investments and insulate against shocks. One approach involves using fiscal stimulus to shore up domestic consumption and to keep inflation positive to allow them to inflate away fiscal deficits in the future. Several economies, including China, have the potential to exercise this option. Japan may also bolster consumption by using fiscal policy to smooth the impact of a slump in US demand.

Market impact: headwinds for stocks and dollar too

The impact of a potential global trade war upon stocks should not be underestimated. As we pointed out in End of “lazy” earnings era may bring fresh opportunities for stock pickers , greater uncertainty, higher volatility and reversals of market-supportive policies may not benefit the average firm. However, we also pointed out in the report that the average firm may not be the optimal vehicle for future value, and that stock selection may begin to reap rewards again. Sector-wise, industries that stand to benefit from domestic stimulus measures implemented by surplus-holding countries could potentially outperform others in such a scenario.

So far, many European nations have committed to increasing government spending, with China also keeping some dry powder to respond to US tariffs. Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba appears to have reacted with alarm to unexpectedly severe US measures; however, his reaction may be an attempt to consolidate support for fiscal countermeasures to shore up newly recovering domestic demand. So long as the prospect of external shocks remains on the horizon, the Bank of Japan may remain on hold until the effects of such shocks on the Japanese economy become clearer. In the longer term, although reserve-holding nations would be loath to see their dollar holdings slump suddenly in value, re-allocation may already be underway, given the dollar's slow but steady decline in terms of its share of global reserves reported by the IMF's Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER).

Should trade flows slow permanently as a result of trade wars, it is possible that the dollar's slump could gather momentum as surplus-holding nations may begin tapping into their reserves to bolster domestic demand. This may also mean that US Treasuries, which have held up for now amid the stock market sell-off, could face higher risk premiums over time. This is because foreign reserve holders, plagued by tariffs, may see less reason to import capital from a slower growing US.