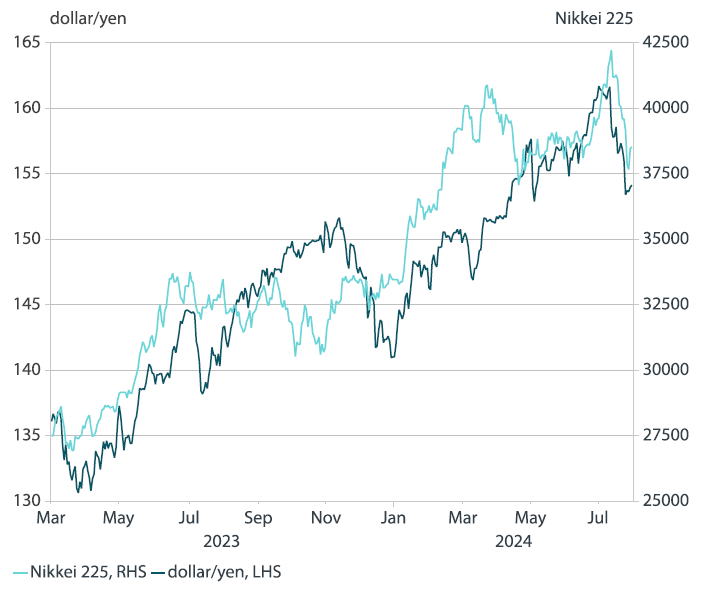

In the past, we have discussed how the weak yen provided a helpful environment for recovery in Japan’s corporate profits, particularly profits of large, listed firms with significant overseas revenues. The Nikkei 225, emblematic of Japan’s largest companies, has for the most part rallied alongside dollar/yen as reflation has taken hold in Japan (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Dollar/yen and the Nikkei

Source: Macrobond

At the same time, we have emphasised many times that yen weakness, however helpful, was not interchangeable with Japan’s structural recovery. For example, we highlighted in our insight, The yen: how weak is too weak? the inflationary pressures that a further trend decline in the yen might invite, which, if unmitigated by other factors, had potential to undermine the “virtuous circle” of domestic price and wage reflation.

In this article, we address yet another facet of yen weakness, one that has undoubtedly been positive for gross national income if not Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP). This is the contribution of the weak yen to Japan’s current account.

The weak yen has been a boost to Japan’s current account

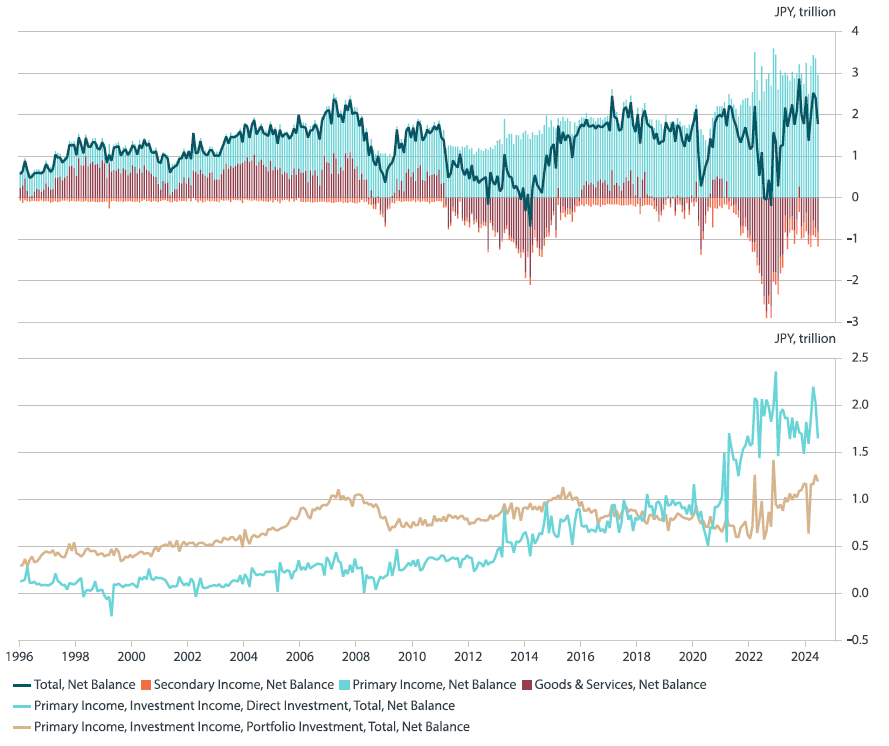

We need look no further than Japan’s ever-larger current account surpluses to see the impact of the weak yen on Japan’s investments abroad. The Japanese current account surplus has changed composition since the first decade of the 2000s, when trade surpluses were still common. We can observe the composition of Japan’s current account in Chart 2, which shows that it has changed markedly in recent years. Following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, Japan’s trade surpluses turned to trade deficits, as the country imported more food, fuel and other goods (alongside some services) than it exported. However, the investments that it made overseas only grew, and earned it more than enough to replace the hole left by net exports. Much of the returns were direct investments by companies (in facilities or offices overseas), and these were then reinvested in the host country. However, a larger portion of the overseas income (up until the pandemic) was derived from portfolio investments, thanks both to overseas growth and a weaker yen.

Today, Japan’s current account surplus is still driven primarily by income from overseas investments. However, corporate pricing power garnered during the pandemic era appears to have stuck. Furthermore, direct investment income, typically reinvested at their respective destinations by corporations, has surpassed portfolio investment income, which still remains sizable.

Chart 2: Japan’s current account surpluses, driven by investment income

Source: Macrobond

FY23 brought extraordinary investment returns for yen-funded overseas investment

Over recent years, yen weakness also transformed good overseas investment returns, which were growing at a faster pace than Japan’s economy, into extraordinary returns. We use a theoretical example of portfolio investment overseas to illustrate how greatly the weak yen is likely to have enhanced already positive investment returns.

In the fiscal year (FY) ending March 2024 the MSCI ACWI offered a favourable total return of 23% with dividends reinvested, while the TOPIX offered just under 5% year-on-year (YoY). Meanwhile, a portfolio of US 7-to-10-year Treasuries would have also enjoyed an unusually high rate of return over the fiscal year, at 17.4% YoY, as US stocks and bonds lost their typically negative correlation. Double-digit returns being achieved in both stocks and bonds is already an unusual state of affairs. However, when coupled with a 26% YoY surge in dollar/yen as of March 2024, an investor holding a significant portfolio of overseas stocks and US bonds could offset some or even all of their potential losses on a minority allocation to Japanese government bonds (JGBs), which most institutional investors also hold.

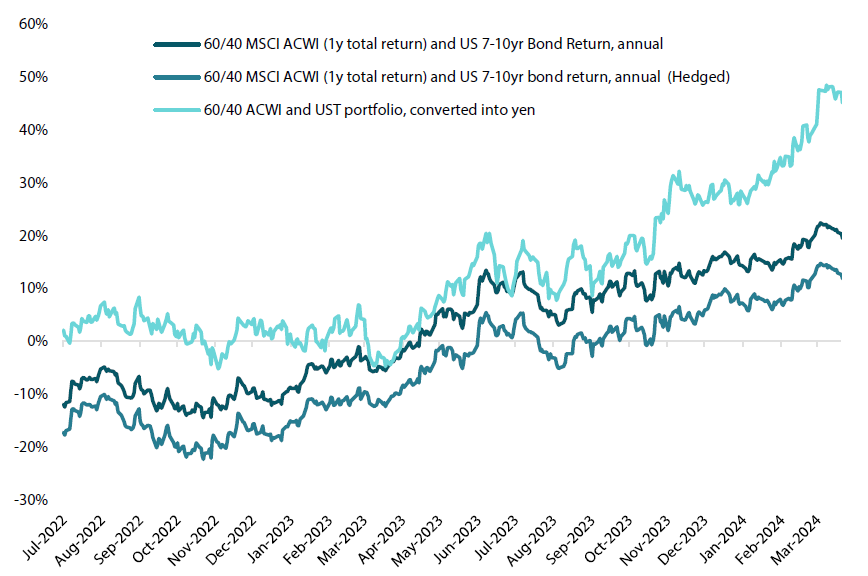

To illustrate the contribution made by a weaker yen as of the end of the fiscal year through March 2024, we present a continuous rebalancing portfolio consisting of 60% ACWI and 40% US Treasuries (Chart 3). Taking a yen-hedged exposure on such a portfolio would have yielded a return exceeding 10%, while an unhedged exposure to such a portfolio would have generated a return of roughly 20% YoY in dollar terms. However, if we were we to convert the dollar returns of this unhedged portfolio back into yen, it would have yielded almost a 50% YoY as of March 2024.

Chart 3: 60/40 stock/bond portfolio, unhedged (funded in yen) and hedged

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM

Small wonder that Japan’s corporate and institutional investors’ income has shown extremely robust growth. However, the yen’s weakness—a prevalent theme until very recently, when the yen “carry trade” saw a sharp reversal—coupled with unusually positive correlations between foreign bonds and stocks, could potentially expose investors’ portfolio vulnerabilities unless they take measures to lock in some of their recent gains amid signs of financial markets eventually changing direction.

Why it would be logical for Japanese investors to trim overseas exposure

Many Japanese corporates and investors are likely to maintain their overseas investments over the long term. However, there are also reasons to assume that returns seen in the fiscal year through March 2024 were exceptional, and it would be a logical medium-term allocation strategy, in our view, for Japanese investors to realise profits on a portion of their foreign asset holdings and reinvest domestically. We outline some of these reasons below.

Fair value (purchasing power parity): Although import prices are no longer as damaging to Japan’s terms of trade as they were in 2022, the yen is significantly below purchasing power parity against many of its trade partners’ currencies. Most notable is probably the dollar/yen. A basket of goods that costs one dollar in the US is worth slightly less than 100 yen in Japan, indicating that purchasing power parity puts dollar/yen at below 100. Although currencies can deviate from purchasing power parity for substantial periods, long-term institutional investors, such as pension funds, should care about purchasing power parity given their role in preserving future pensioners’ purchasing power. The undervaluation of the yen, which appeared extreme until recently, should thus send signals to institutional investors to consider realising profits on some of their non-yen assets. This is due to the medium to long-term likelihood of a reversal in the yen's weakness from excessively low levels.

Portfolio diversification: Japanese investors’ extraordinary returns can be partially attributed to the yen. However, it also be attributed to the strong returns of equity markets, both foreign (with a high US weighting) and domestic. A part of this foreign equity portfolio is likely to have inherited some of the high concentration in large cap tech names characteristic of US equity indices. That said, Japan, with its cash-rich corporates and chronic labour shortages, may be a prime customer for these firms’ productivity-enhancing technologies. As such, there may be a persistent strategic case for Japan to maintain investments in the US tech sector. Japan’s reliance on overseas technology—especially US—is meanwhile evident elsewhere in the country’s balance of payments. This includes Japan’s “digital deficits” and the software investments that are particularly common among firms in labour-intensive sectors reporting skilled labour shortages. Therefore, US equities might not be where domestic investors should make their largest cuts, even if they trim exposure elsewhere.

US Treasuries, meanwhile, have lost their negative correlation with US stocks and are therefore less effective as portfolio diversifier than they were in past years. Indeed, maintaining a high weighting in overseas stock requires an effective portfolio diversification strategy. In addition, there are currently no signs of the US adopting fiscal discipline, and this could potentially roil the longer end of the US Treasury curve. This is without even factoring in political risks related to trade conflicts or other potentially inflationary protectionist measures. Japan’s foreign bond allocation, both hedged (which falls under domestic bonds) as well as unhedged, may be ready for a reduction, possibly until investors are presented with better levels for entry. It may be logical for institutions to partially substitute hedged foreign bonds with JGBs, but it may be better to do so at a pace that allows for greater purchases when yields rise. The BOJ is on a hiking path (so long as domestic demand remains positive), so JGBs may be serve a more defensive/diversification strategy role rather than achieve strong gains.

Longevity hedging–strategic stock investments: The reasons why Japan’s pension funds may want to retain many of their foreign stock investments are somewhat similar to why domestic investors in general should accumulate domestic stock investments. One big factor influencing future pensioners’ purchasing power is longevity, which in Japan, is significantly higher than many other economies. Bond ladders are typically poor instruments in an economy of rising longevity, especially when inflation is positive. Conversely, stock returns in non-deflationary economies tend to compound over time, while their volatility increases at a slower rate (the square root of time). The longer the compounding period, the longer the portfolio is likely to last under decumulation. Consumers currently hold very low proportions of stock and still have an outsized cash allocation (over 50% of household balance sheets). Institutional investors, who are responsible for protecting future household purchasing power, therefore have every reason to try to diversify in ways that domestic investors are not yet doing themselves, as household portfolio adjustments are likely to take time to manifest.

Japan’s structural reform: Japan is exiting deflation, and its cash-rich companies are reallocating their balance sheets in ways that are conducive to boosting returns on equity. Japanese equity valuation remains more in line with recent history than that of the ACWI, suggesting that it may be prudent to remain invested in Japanese stock. Moreover, there is potential for sector rotation once real wages enter and stay in positive territory (most recent data showed real wages entering positive territory, rising 1.1% YoY in June 2024) and consumer behaviour consequently changes. As consumption then accelerates, there could be some catch-up growth in sectors that have been overlooked to date. Support for domestic sectors (who were hurt by yen weakness and its impact on imports) may provide a buffer for Japanese portfolios even if there is some yen appreciation or growth slows abroad.