This morning, I passed by the building where I used to work in downtown Singapore. A certain European global investment bank, the anchor tenant until 2023, is no longer there but the dental practice that occupied a single unit on the first level remains.

Medicine is an evergreen industry, intertwined with the economies of all nations worldwide. As long as we continue to face the limits of our mortality, we will need therapeutics to treat diseases.

The research and development of novel drugs, also known as innovative drugs, was historically dominated by large companies in the West. These companies, colloquially termed “Big Pharma”, enjoy exclusive rights to market novel drugs for a set period due to patent protection laws. After these patents expire, other manufacturers can apply for regulatory permission to make copies of these medicines, known as generic drugs.

India has always been the manufacturing base for generic drugs, due to lower production and labour costs which help keep these drugs affordable to the regions where they are distributed. The country is the largest supplier of generic drugs with a 20% global market share in 2023.

Having established a strong foothold in small molecules drugs, or the oral solids market, Indian drugmakers are starting to make inroads into the field of injectable medicines including large molecule biologic drugs. Historically, these companies faced difficulty entering the injectables market due to the more stringent compliance and quality control requirements in manufacturing biologic drugs. In fact, from 2014 to 2018, many Indian pharmaceutical companies faced significant challenges related to non-compliance issues with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These resulted in a range of regulatory actions, from warning letters to import alerts. In cases of repeated serious violations, plants were placed under consent decree. The key issues raised by the FDA focused on the lack of data integrity, inadequate quality control procedures and poor documentation. This resulted in delayed generic drug approvals, supply disruptions and reputational damage to the industry.

Aware of these challenges, Indian pharmaceutical companies spared no effort to embark on corrective and preventive action plans. These were designed to investigate quality issues, identify root causes and for necessary actions to be taken in order to rectify problems and prevent their recurrence, thereby re-establishing their track record. Many Indian pharmaceutical companies hired former FDA officials to scrutinise their production plants, review plant designs and manufacturing processes, ramp up quality control and address data integrity issues, as per our channel checks.

The industry took a few years to work through their FDA regulatory issues. Starting from 2019, many Indian pharmaceutical plants began to emerge from remediation and become compliant with FDA standards. This proved timely, not just for India but also for the world. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Indian pharmaceutical companies played a crucial role in supplying essential life-saving medicines, antiretroviral drugs and vaccines globally. Officially, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 7 million people died from COVID-19. We believe that without the help of Indian pharmaceutical sector, the death toll could have been much higher.

By mid-2023, the WHO declared an end to the global Public Health Emergency for COVID-19. However, the world is now facing uncertainty on another front—geopolitics. As the US and its allies attempt to keep China in check in the battle for technological and geopolitical dominance, companies eager to avoid being caught in the crossfire are looking to shift business away from the “factory of the world” in what is known as the “China plus one” strategy. In 2024, US lawmakers introduced the BIOSECURE bill. This legislation aimed to restrict entities that receive US federal funding from contracting with certain Chinese biotech companies in order to safeguard sensitive genetic data of US citizens from exploitation by a “foreign adversary” for surveillance or espionage. Despite passing the US House of Representatives with bipartisan support in September 2024, the legislation failed to make it through Congress before the year end. Currently the fate of the bill remains uncertain.

We see two scenarios unfolding from these events. Firstly, this presents a challenge and also an opportunity to Indian companies as they source a significant portion of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from China. To mitigate the issue, Indian authorities have been rolling out “Production Linked Incentive” programmes. These provide capital expenditure for drug companies to build factories to process the raw materials, known as intermediates, used to produce APIs, and to manufacture the APIs themselves. Their efforts may be starting to bear fruit. In April 2024, Indian pharmaceutical company Aurobindo Pharma commissioned a major manufacturing plant for Penicillin-G and 6-APA, which are key intermediate compounds in the synthesis of common antibiotics such as amoxicillin. Aurobindo’s plant, which is projected to meet 20% of global demand when operating at full capacity, has started trial production.

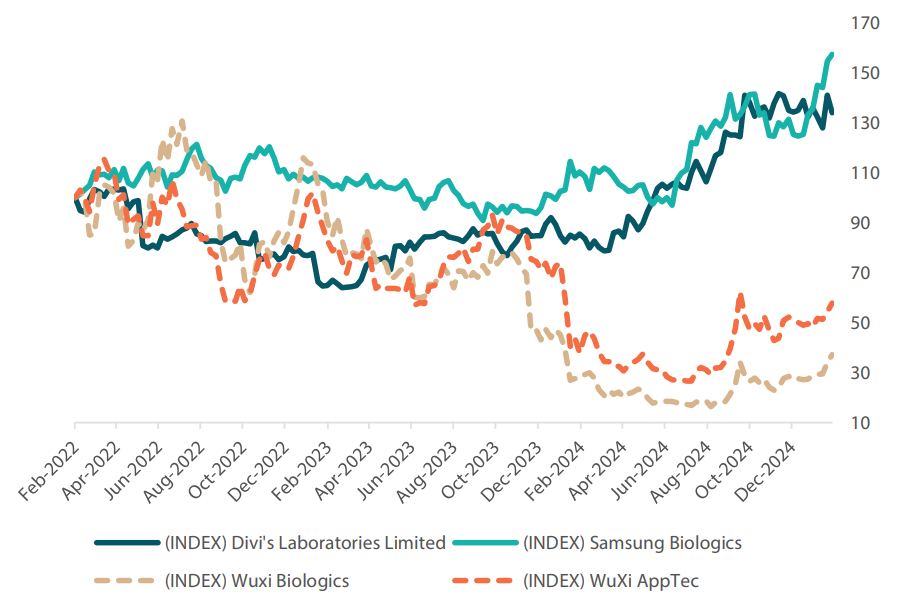

Secondly, Indian contract, development and manufacturing organisations (CDMOs), such as Divi’s Laboratories, are poised to gain market share in biopharma outsourcing from Big Pharma at the expense of their Chinese counterparts (Chart 1). The proposed US BIOSECURE bill specifically targets companies such as Wuxi AppTec and Wuxi Biologics, both of which are key service providers to Big Pharma. Even though the passage of the bill through Congress remains uncertain, many US companies are considering shifts to diversify away from Chinese CDMOs in order to mitigate risks should the bill be reintroduced in Congress in the future.

Chart 1: Clear bifurcation of the sector since the US BIOSECURE bill was first proposed in January 2024

Rebased to 100 in February 2022

Source: FactSet, January 2025

To capitalise on this opportunity, we believe Indian CDMOs need to increase their process development and biomanufacturing capabilities, further improve quality standards and build manufacturing capacity of sufficient scale, especially in more advanced and higher value modalities such as biologics, peptides and cell and gene therapy.

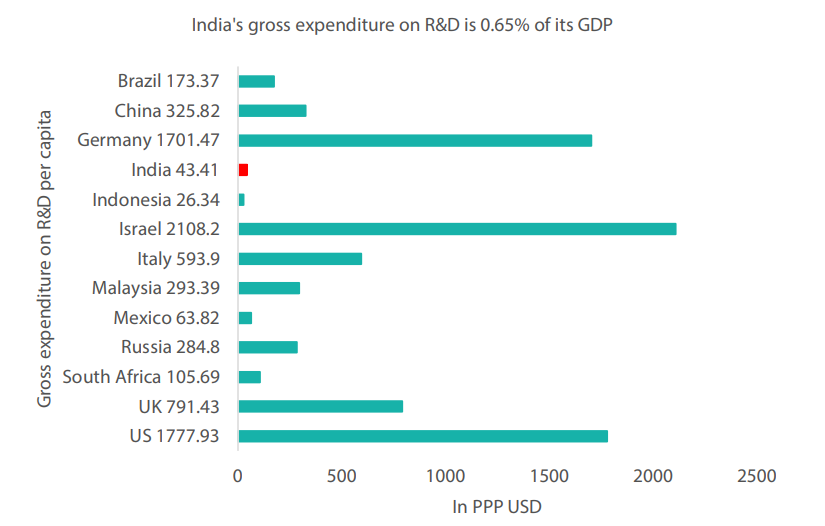

Beyond this, to create a self-sustaining ecosystem for life sciences and drug development, we believe that it is crucial for Indian regulators to implement necessary measures in order to create a biomanufacturing hub. Such a hub would bridge the translational gap between laboratory and clinical practice, enabling India to transition from a low-cost generic drug maker to a vibrant centre for biomanufacturing. Some of these measures may include an effective legal framework for intellectual property rights protection, capital market support and government incentives to encourage entrepreneurship and accelerate research and development (Chart 2).

Chart 2: India’s research and development (R&D) spending is one of the lowest in the world

Source: News18 Creative, July 2022

In retrospect, we have seen this play out in South Korea two decades ago, and in China over the last 10 years. We believe Indian drugmakers have the potential to make this transition, supported by latent demand from a huge domestic market, private enterprises hungry for success and a large talent pool of science, technology, engineering and medicine graduates. According to statistics from the World Population Review, India had the third-largest number of doctorates awarded in 2024, coming after the US and China.

Indeed, we have observed that some Indian pharmaceutical companies such as Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, are already moving in that direction through in-licensing speciality drugs. We view these initiatives by Indian firms as a crucial intermediate step to build the required expertise in drug development before advancing into innovative drug research.

Aside from the Indian pharmaceutical industry, the rapid growth in the Indian private hospitals sector is also noteworthy. According to a 2024 Lancet report, India has the lowest healthcare spending among G20 countries despite being the world’s fifth-largest economy. Government expenditure on healthcare was described as “an abysmal 1.2% of gross domestic product (GDP)”, and out-of-pocket expenditure remains elevated.

In India, a shortage of public hospitals means private operators will have to step in to bridge the gap. Taken at a hospital waiting area during a road trip in Hyderabad, March 2024.

Credit: Kathy Ng, March 2024

Health insurance penetration in India has seen a dramatic increase over the last decade, driven by rising healthcare costs, increased affluence and heightened awareness. Indian private hospitals present a structural opportunity to tap into this longer-term secular growth trend as the pool of people with health insurance expands. This is expected to boost both inpatient and outpatient volumes and utilisation, even as new bed capacities are added over the next three years. To put things in perspective, in 2015, there were only two listed investable Indian hospital operators, Apollo Hospitals and Fortis Healthcare, and there were no listed pharmacy or diagnostics companies. Since then, their numbers have grown exponentially, with more than 20 hospitals and diagnostics chains now listed.

Pharmacies dispensing medicines, offering health checks and diagnostics. Taken on a road trip in Hyderabad, March 2024.

Credit: Kathy Ng, March 2024

While there might be some near term concerns over US President Donald Trump’s threats to impose tariffs of roughly 25% on pharmaceutical imports, we believe these are unlikely to materialise. The Indian government is already making plans to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement with the US, focusing on specific sectors and possible tariff concessions.

With the stars aligning for the Indian healthcare sector, it is little wonder that the world’s fifth largest economy is poised to take its place among the top three healthcare markets globally by 2030. We expect demographics to provide a solid tailwind for healthcare expenditure in the days ahead. This is due to chronic government underspending in the sector, rising life expectancies, increasing disposable incomes and rising insurance coverage as India’s GDP continues to expand. We have identified key Indian healthcare companies that are well-positioned to tap into these growth drivers in our various investment vehicles.

While it may take time for these developments to bear fruit, we firmly believe that the necessary fundamental changes have been set in motion and will lead to long term, sustainable investment opportunities within the Indian healthcare sector.

Any reference to a particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security. Nor should it be relied upon as financial advice in any way.