The Nikko Asset Management Global Equity team philosophy is based on the belief that investing in ‘Future Quality’ companies will lead to outperformance over the long term. This paper draws on academic evidence to outline the three fundamental concepts which underpin our definition of ‘Future Quality’ investments.

Firstly, we look at value creation models within firms. We assess the level of excess cash return on invested capital earned by firms and the sustainability of those returns into the future by looking at the importance of a firm’s competitive advantage period.

Secondly, we analyse past stock market returns to highlight that it is not merely the level of excess cash return on invested capital earned by a company that drives shareholder returns. Rather, the market rewards companies that can allocate capital to improve cash returns on investment and maintain their competitive advantage.

Finally, we assess the role of growth and its impact on shareholder returns for businesses with high, medium and low cash return on invested capital structures.

Drawing on this academic research, we explain in detail what we mean by ‘Future Quality’ and why we believe it leads to long-term outperformance. If an investor can anticipate a meaningful positive change in excess return (cash return on invested capital less cost of capital), identify firms that have a longer competitive advantage period than the market anticipates and can reinvest those excess returns into the business (growth), they should generate shareholder returns above the market. These are the characteristics of a ‘Future Quality’ company.

Definition of ‘Future Quality’

We define ‘Future Quality’ as a business that can generate sustained growth in cash flow and high and improving returns on invested capital at attractive valuations. Our portfolios are only comprised of companies that exhibit these characteristics and our research is devoted to unearthing companies that meet this criteria.

This concept underpins everything we do in the Global Equity team and the debate as to whether a new idea is eligible for the portfolio or an existing holding should be sold, hinges on a stock’s ‘Future Quality’ characteristics and merits. In identifying ‘Future Quality’ companies, we analyse a number of variables. We focus on the quality of management, the quality of the franchise, the quality of the balance sheet and combine this with a disciplined valuation approach.

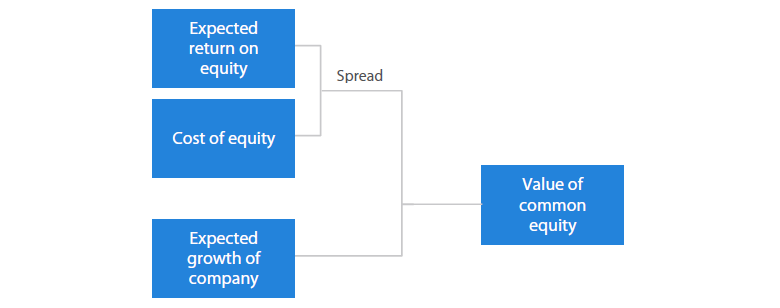

Figure 1: Future Quality definition

Source: Nikko AM

Excess return and the competitive advantage period

Firms create value by generating a spread between their cash return on invested capital (CROIC) and their cost of capital. The length of time this spread or excess return can be earned by a company is known as its competitive advantage period. Forecasting the sustainability of this spread (competitive advantage period), the magnitude (excess return) and the ability to reinvest the excess return into the business (growth) are key to determining ‘Future Quality’ attributes.

Focusing on the sustainability of excess returns and improvements in CROIC is vital. The market rewards companies that can improve returns and maintain their competitive advantage. In his paper titled ‘Do Your Business Units Create Shareholder Value?’ Professor Enrique Arzac of the Columbia Business School described this concept as the Simple Value Creation Model.1

Figure 2: The Value Creation Model

Source: Professor Enrique Arzac, Harvard Business Review. *Spread = Excess return on equity above cost of equity

Arzac identified the importance of the sustainability of that excess return in valuation. Management’s decision making should focus on allocating capital to business units that can generate excess returns over the long term. Similar studies have explored the concept of value creation over the years. Professor William Fruhan (Harvard Business School) in his book ‘Financial Strategy: Studies in the Creation, Transfer, and Destruction of Shareholder Value’2 concludes that the only way to increase the value of an asset is to influence either the cash flow derived from that asset or the discount rate (weighted-average cost of capital). He further explains that the profitability of a firm is based on the capital intensity, profit margins and leverage and that the value of the firm is determined by the excess return, growth and the competitive advantage period. Hogan et al3 (1999) pointed out that shareholder value is created when a company invests in projects that earn a return in excess of the cost of capital.

Value creation and share prices – are high returns on invested capital all that matter?

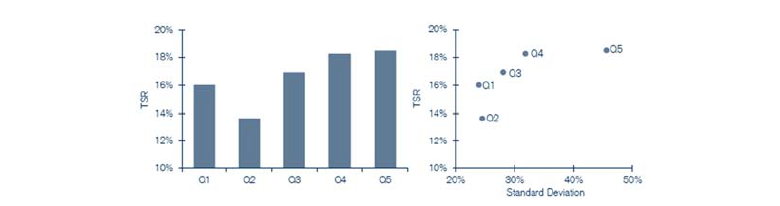

Buying the best or worst quality company based on historical returns is a poor strategy. Empirical evidence shows that high or low return businesses exhibit very little correlation to future shareholder returns. Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan4, from Credit Suisse HOLT, carried out a 10-year study looking at historical returns and forward share price returns. The universe (1,355 US companies excluding financials and utilities) was divided into quintiles based on HOLT’s cash flow return on investments (CFROI) in 2002, with quintile 1 (Q1) being the best return businesses and quintile 5 (Q5) being the worst. Figure 3 shows the performance of each quintile over the subsequent 10-year period. This suggests that low quality companies (as defined by historical returns) perform well and even better than their high quality counterparts; however, when risk adjusted, there is no discernible pattern. The Sharpe ratios for Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4 and Q5 were 0.45, 0.34, 0.42, 0.41 and 0.29, respectively.

Figure 3: Total shareholder returns (2003-2012) by quintile based on 2002 CFROI ranking

Source: Credit Suisse HOLT and FactSet

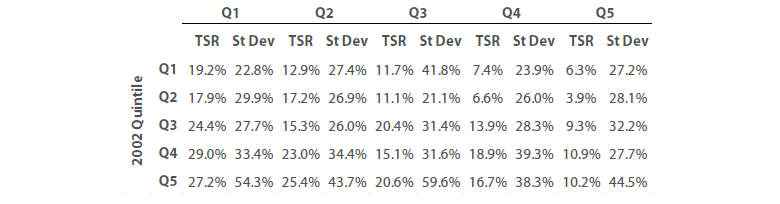

However, improving future returns is a very powerful driver of share prices. Using the same sample, Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan5 found that the stocks with the largest improvement in returns over the 10-year period (i.e. moved from Q5 to Q1) delivered the highest returns and stocks that migrated from the top quintile to the bottom quintile delivered the weakest returns. This suggests future cash return on investment matters most.

Figure 4: Total shareholder returns (2003-2012) for all 2002 to 2012 quintile combinations

Source: Credit Suisse HOLT and FactSet

Importantly, the persistence in high returns together with improvements in return, which is integral to a firm’s competitive advantage period, is a bigger driver of future shareholder return. Looking at the same data, those stocks that showed persistence in high returns over the period had higher returns and a significantly higher Sharpe ratio. Stocks that started in Q1 and remained in Q1 for the 10-year period delivered a total shareholder return of 19.2% with a standard deviation of just 22.8%. These companies essentially ‘beat the fade’ or had a longer competitive advantage period than the market forecast.

If an investor can anticipate a meaningful positive change in excess return (cash return on invested capital – cost of capital), identify firms that have a longer competitive advantage period than the market anticipates and can reinvest those excess returns into the business (growth), they will generate shareholders returns above the market. These are the characteristics of a ‘Future Quality’ company.

The importance of growth

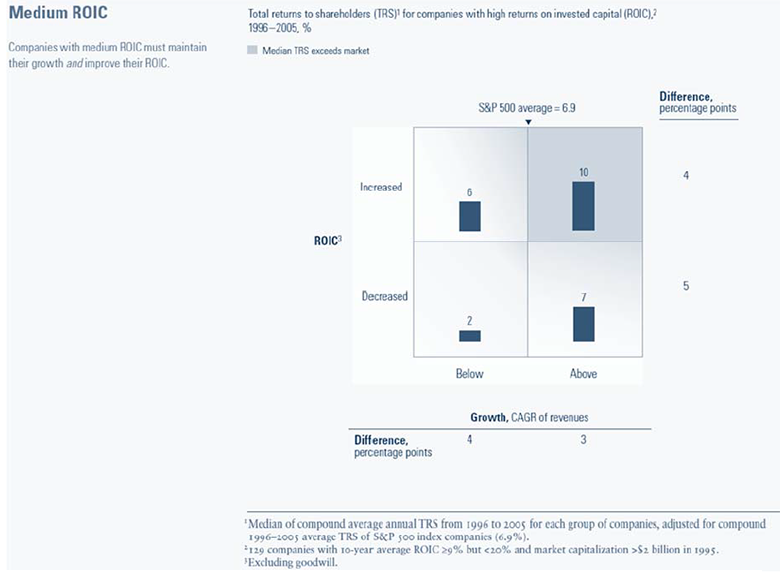

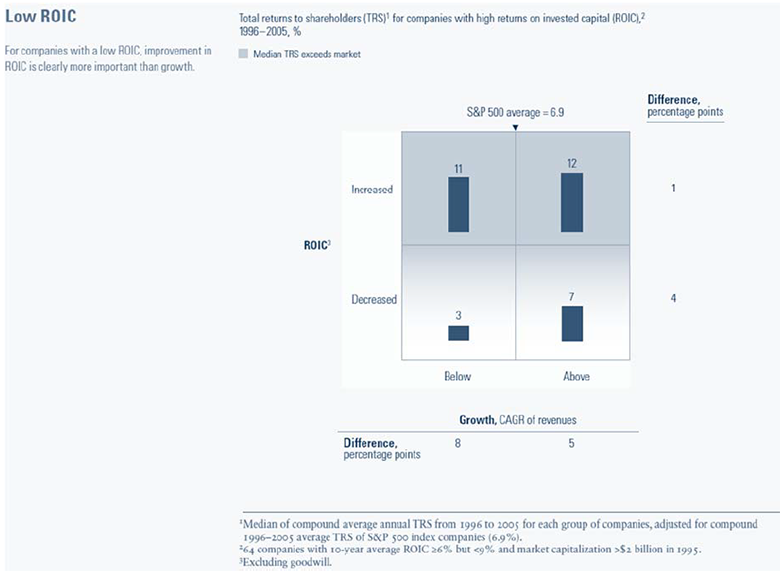

This concept was explored further by McKinsey’s Bing Cao, Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller6 – ‘Balancing ROIC and growth to build value’ and in Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller7– ‘How to choose between growth and ROIC’. This work explored the relationship between total returns to shareholders and the change in return on invested capital (ROIC). However, they took this a stage further and also incorporated the impact of growth (as defined by change in revenues). They identified high correlations between value creation, growth and returns and showed that if companies grew faster and increased returns more than the market, they subsequently outperformed the market.

These two studies highlight the importance of focusing on changing profitability as a driver of share price returns. Neither study, however, incorporated a cost of capital or discount rate due to the inherent challenges of assigning an appropriate cost of capital to individual companies in an empirical exercise. True wealth creation does not come from the absolute level of ROIC but from the spread between returns and the cost of capital. Wenner and LeBer8 in 1989 spoke of the importance of management’s focus on shareholder value analysis (SVA) – the process of analysing how business decisions affect a company’s economic value (net present value of the expected cash flows discounted at the cost of capital). They emphasised that long-term cash generation is rewarded by the market, not growth for growth’s sake or earnings per share.

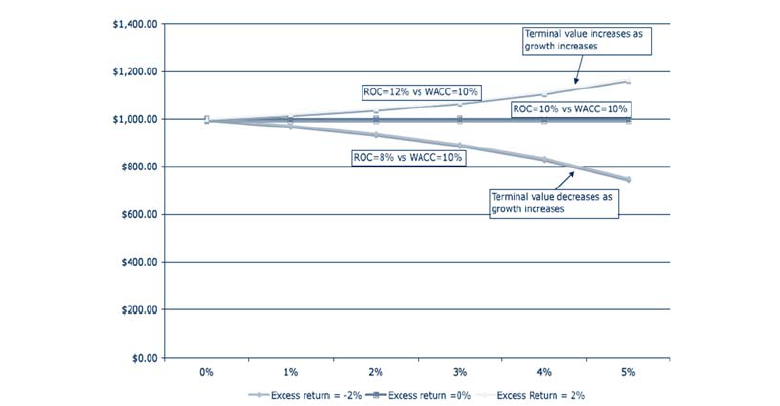

It is also important to understand the relationship between growth and excess returns. When a company is generating excess returns, growth will be rewarded. When a company is generating returns below the cost of capital (i.e. destroying value), growth will be penalised. In the example shown in Figure 5, Aswath Damodaran9, Professor of Finance at New York University Stern School of Business, highlights the change in terminal value based on changes in growth and excess returns. If a company is generating returns in line with its cost of capital, growth will not be rewarded or penalised, i.e. the terminal value will remain unchanged.

Figure 5: Change in terminal value based on changes in growth and excess returns

Source: Aswath Damodaran, Stern School of Business

Cash-based measures of value creation

We focus on CROIC, rather than the return on equity metric used in Arzac’s10 Value Creation Model and Fruhan’s11 study. Cash flow is a better measure of profitability than reported or operating earnings and has a higher predictive power than the other two measures in terms of shareholder return. Kenneth Hackel, Joshua Livnat and Atul Rai12 have written extensively on the subject and demonstrated that investment strategies based on free cash flows have merit.

Models linking cash returns and cost of capital, also known as value-based measures, started to evolve meaningfully about 30 years ago and this forms the basis of our analysis. The best known value-based measures are economic value added (EVA), cash flow returns on investment (CFROI), shareholder value added (SVA), economic margin (EM) and cash value added (CVA). For more detail on each of these, Daniela Venanzi13 in ‘Financial Performance Measures and Value Creation: the State of the Art’ is a good reference. The other benefit of these value-based measures is that they allow investors to compare corporate performance and profitability globally. Accounting differences between regions are reconciled and given the cost of capital is embedded in some of these calculations, a clear comparison can be made between firms around the world.

We have identified that improving and sustainably high cash returns are correlated with positive relative share price returns and this is enhanced when combined with growth.

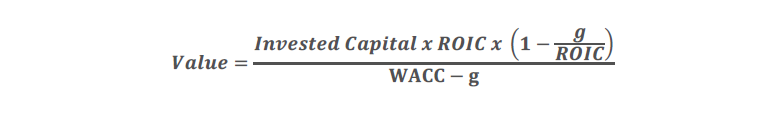

It also requires a robust valuation framework to identify the most attractive opportunities. Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart and David Wessels14 in ‘Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies’ discuss the value-based concepts in detail and define the fundamental principles of value creation.

Figure 6: ROIC & Growth Drive Multiples

Source: Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart and David Wessels

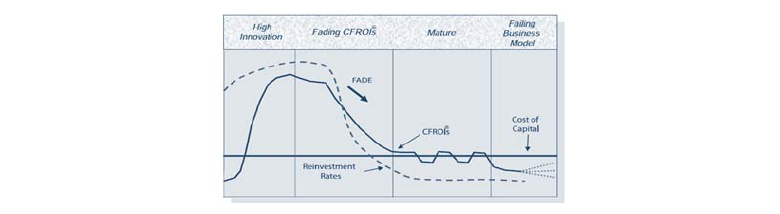

The above calculation sets a framework, but assumes growth and ROIC remain constant in perpetuity. It doesn’t integrate an appropriate competitive advantage period, after which returns would fade towards the cost of capital. This can be addressed in part by incorporating a two-stage discounted cash flow model with appropriate terminal assumptions. Many value-based valuation models, including CFROI and economic margin (EM), incorporate a specific competitive advantage period over which a company can generate excess return after which returns will fade towards the cost of capital or weighted-average cost of capital. This is appropriate as most high return businesses and industries will attract competition and returns will erode over time; similarly, low return businesses / industries will see players exit the industry and returns can rise over time. Aswath Damodaran15

outlined these concepts in his paper ‘Return on Capital (ROC), Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), and Return on Equity (ROE): Measurement & Implications’.This is the theory behind HOLT’s Competitive Life-Cycle Framework as outlined below and analysed by Bart Madden16 in ‘Maximising Shareholder Value and The Greater Good’. A typical firm will move through four phases of profitability and growth through its life.

Figure 7: HOLT’s Competitive Life-Cycle Framework

Source: Credit Suisse HOLT

To value the company appropriately an investor must forecast economic cash returns, growth, required operating assets and the competitive advantage period.

His work highlighted that in the majority of cases, positive shareholder returns are associated with ‘surprising’ positive patterns of actual fade in relation to earlier expected patterns for that period and vice versa. In other words, the company was able to grow and generate excess returns for longer than expected, so the competitive advantage period was longer than the market forecast.

Earll Murman et al17 in the book ‘Lean Enterprise Value’ stated: “Understanding value creation is not difficult, but determining the specific actions to create value can be more complex and a challenge, especially in a changing world”. The challenge for investors is identifying companies that will have long competitive advantage periods through which they can sustain high and / or improving cash returns, in other words identify ‘Future Quality’ investments. The majority of global companies will not exhibit these characteristics. Only a fraction of companies within the global universe can be considered ‘Future Quality’ or display some ‘Future Quality’ characteristics.

In summary, value-based profitability measures are better at identifying corporate performance. The change in these profitability measures, growth and the competitive advantage period are key drivers of future share price performance and the capital allocation decisions of management will impact both.

How Nikko AM’s Global Equity team identify ‘Future Quality’

Recognising ‘Future Quality’ requires long-term fundamental analysis and creative research. To evaluate whether an individual investment may meet our ‘Future Quality’ criteria, we focus on the quality of management, the quality of the balance sheet and the quality of the franchise as a basis for modelling and quantifying the spread between CROIC and the cost of capital, growth and forecasting the competitive advantage period. Understanding the business, the capital intensity of the business, the strategy and the structure of the market allows for more accurate forecasts. Understanding the quality of the franchise helps us make more informed assumptions on growth rate, profitability and the competitive advantage period of the company. Michael Porter18 has written extensively on this subject. In his “value chain approach”, he argued that the profitability of a firm is influenced by its industry structure (quality of the franchise) and the strategic decisions (quality of management) it makes. A firm’s profitability is influenced by industry attractiveness (Porter’s19 five competitive forces) and the firm’s position within that industry will dictate whether it can generate above-industry or below-industry returns (competitive advantage period).

In assessing the quality of management, we seek to identify a strong and consistent strategy, good corporate governance, identifiable and aligned incentive programmes, an excellent track record and disciplined capital allocation. Ideally all stakeholders should benefit from management actions as this will ensure a more sustainable business. The quality of management is integral to understanding the sustainability of a firm’s competitive advantage period. Management’s capital allocation decisions will have a meaningful impact on the competitive advantage period and the ability to generate excess returns. This is clearly a crucial factor in the financial outcome for shareholders.

The quality of balance sheet underpins a company’s growth aspirations. A strong balance sheet will be able to finance profitable growth and make the management team’s capital allocations decisions far easier. Investors must focus on funding sources and the cost of that funding, the leverage within the business and working capital requirements and changes.

Quality of valuation. Analysis of the balance sheet, management and franchise allow us to forecast growth, margins and asset turns of the business, the capital expenditure and funding requirements, the competitive advantage period and cost of capital. These are the key components to calculate future CROIC and the value of the firm and allow us to make an informed decision as to whether a potential investment is ‘Future Quality’ and is valued attractively.

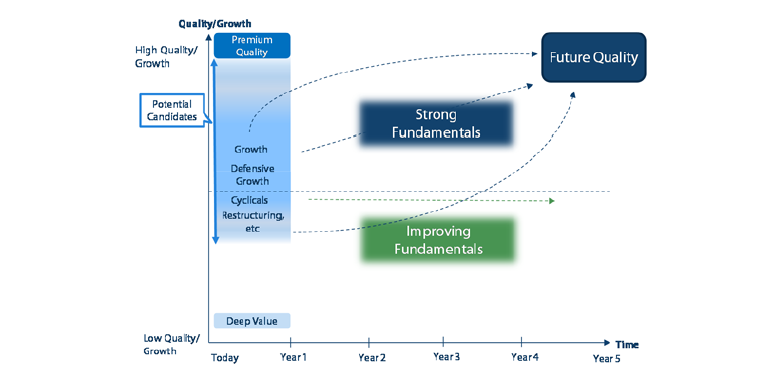

‘Future Quality’ companies should outperform the market over the long term

Future Quality investing aims to identify companies that can generate superior or improving cash returns above the cost of capital and have competitive advantage periods longer than the market anticipates. The chart in Figure 8 illustrates this. Future Quality businesses with ‘Strong Fundamentals’ generate high returns on invested capital today which we forecast to be sustainable due to their extended competitive advantage position. These are companies that can “beat the fade” in returns.

Figure 8: Future Quality Companies

Source: Nikko AM

Companies that have ‘Improving Fundamentals’ are generating lower returns on invested capital today but we expect to generate substantially higher returns in the future. These are companies that we forecast to surprise positively as they generate incrementally better returns over time. Regardless of the starting point, Future Quality investing is about identifying companies that can attain and sustain high returns on investment in the future. We believe a portfolio of ‘Future Quality’ companies should outperform the market over the long term.

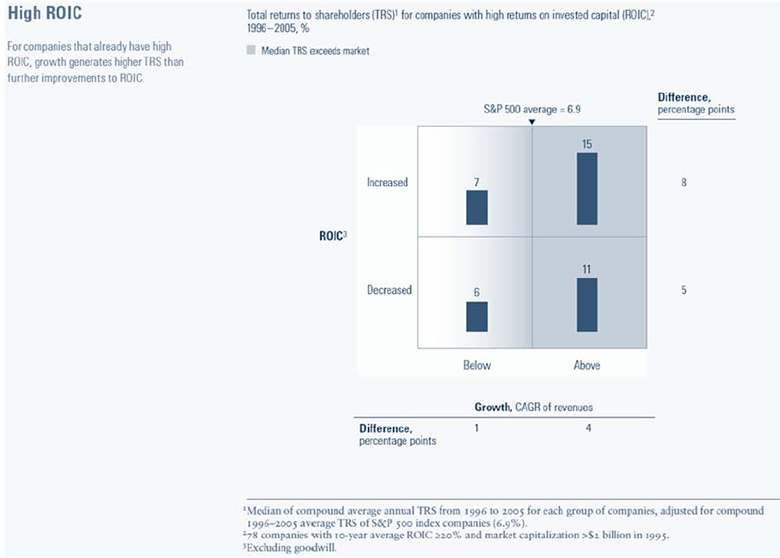

Appendix 1: How to choose between growth and ROIC

Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller20 explored the relationship between total returns to shareholders and the change in ROIC. However, they took this a stage further and also incorporated the impact of growth (as defined by change in revenues). They identified high correlations between value creation, growth and returns. They looked at High ROIC, Median ROIC and Low ROIC companies and analysed the dynamics of these companies over a 10-year period (1995-2005) when growth and returns improved more or less than the market.

Figure 9: High ROIC

Source: Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller

Figure 10: Medium ROIC

Source: Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller

Figure 11: Low ROIC

Source: Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller

Footnotes

- Enrique R. Arzac, “Do Your Business Units Create Shareholder Value?” - Harvard Business Review January – February 1986 pp. 123

- William E. Fruhan, Jr., Financial Strategy: Studies in the Creation, Transfer, and Destruction of Shareholder Value - Homewood 1979 pp. 7-15

- James Hogan, Robert Neyland and Mark Greslee, “Creating Shareholder Value” – Electric Perspectives, September/October 1999 pp. 44-54

- Michael J. Mauboussin and Dan Callahan, Economic returns, Reversion to the Mean and Total Shareholder Returns – Anticipating Change is Hard but Profitable, Credit Suisse Global Financial Strategies 2013 pp. 2-7

- Michael J. Mauboussin and Dan Callahan, Economic returns, Reversion to the Mean and Total Shareholder Returns – Anticipating Change is Hard but Profitable, Credit Suisse Global Financial Strategies 2013 pp. 2-7

- Bing Cao, Bin Jiang, and Timothy Koller, “Balancing ROIC and growth to build value” - McKinsey on Finance Spring 2006

- Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller, “How to choose between growth and ROIC” - McKinsey on Finance Number 25 Autumn 2007 pp19-22

- David Wenner and Richard Leber, Managing for Shareholder Value – From Top to Bottom (Harvard Business Review, November – December 1989)

- Aswath Damodaran, “Return on Capital (ROC), Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), and Return on Equity (ROE): Measurement & Implications” – Stern School of Business July 2007 pp62-64

- Enrique R. Arzac, “Do Your Business Units Create Shareholder Value?” - Harvard Business Review January – February 1986 pp123

- William E. Fruhan, Jr., Financial Strategy: Studies in the Creation, Transfer, and Destruction of Shareholder Value - Homewood 1979

- Kenneth Hackel, Joshua Livnat and Atul Rai, “A Free Cash Flow Anomoly” Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance Volume 15 Winter 2000

- Daniela Venanzi, “Financial Performance Measures and Value Creation: the State of the Art” Springer Milan Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York 2012 pp. 13-30

- Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart and David Wessels, “Valuation – Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies” - McKinsey & Co 4th Edition pp66

- Aswath Damodaran, “Return on Capital (ROC), Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), and Return on Equity (ROE): Measurement & Implications” – Stern School of Business July 2007 pp53-60

- Bart Madden, “Maximising Shareholder Value and the Greater Good” – LearningWhatWorks 2000 pp. 7-10

- Earll Murman et al, “Lean Enterprise Value” – Palgrave Macmillan / The Lean Enterprise Foundation 2002 pp. 177

- Porter, Michael, "Competitive Advantage" – The Free Press. New York 1985 pp 11-15

- Michael Porter, “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy” – Harvard Business Review, March/April 1979. Pp137-145

- Bin Jiang and Timothy Koller, “How to choose between growth and ROIC” - McKinsey on Finance Number 25 Autumn 2007 pp19-22